THE ATLANTIC

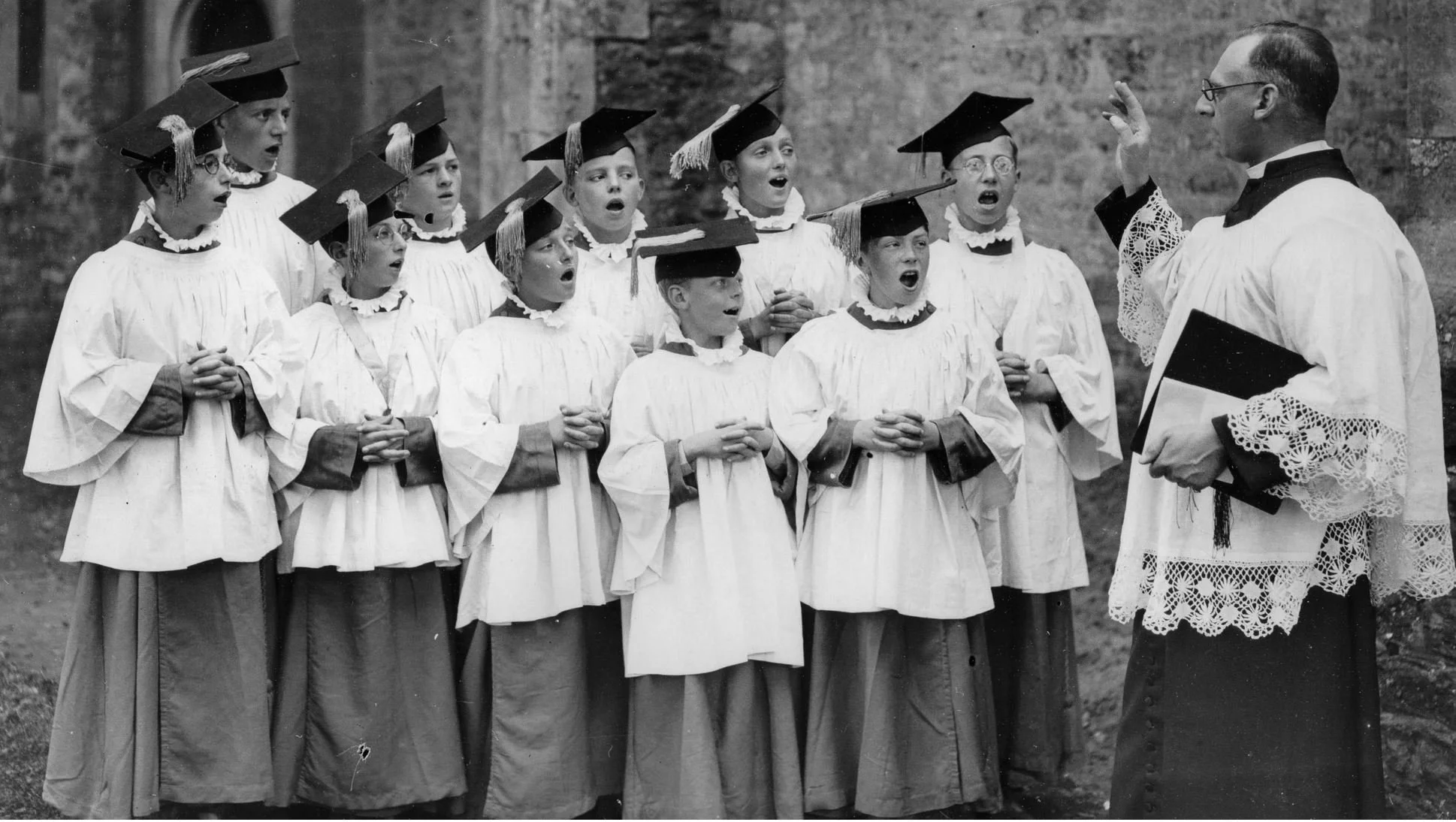

How Communal Singing

Disappeared From American Life

March 28, 2012

And why we should bring it back

With the crack of baseball bats across the land, the singing season for Americans is about to begin. At ballparks from Saint Louis to San Diego, people will stand during the seventh-inning stretch and belt "Take Me Out to the Ballgame." They will feel the pleasure of singing a bouncy, easy song with thousands of other fans. They will be cheered by the sunny lyrics, even if their team is down. They will lose themselves in a bond stretching around the stadium, a few minutes of carefree unity. And when the season's over, that'll be it until next spring.

Adults in America don't sing communally. Children routinely sing together in their schools and activities, and even infants have sing-alongs galore to attend. But past the age of majority, at grown-up commemorations, celebrations, and gatherings, this most essential human yawp of feeling—of marking, with a grace note, that we are together in this place at this time—usually goes missing.

The reasons why are legion. We are insecure about our voices. We don't know the words. We resent being forced into an activity together. We feel uncool. And since we're out of practice as a society, the person who dares to begin a song risks having no one join her.

This is a loss. It's as if we've willingly cut off one of our senses: the pleasure center for full lungs and body resonance and shared emotion and connection to our fellow man. When the crowd at Fenway Park sings Neil Diamond's "Sweet Caroline" (in an inexplicable Red Sox tradition), there's really nothing comparable to that feeling of 30,000 people stepping down three notes in giddy unison, "Oh–Ohh–Ohhhh."

Clearly we need the outlet of singing—witness the karaoke-bar boom—but as civic engagement declined, our store of true folk songs evaporated. You can blame all the usual causes for withering "social capital," from dependence on electronic entertainment, to lengthening work days that reduce free time, to an ever more diverse society, in which your songs are not mine. The elevation of the American Idol model and the demotion of the casual crooner is a real discouragement to amateurs as well. Because we're out of the habit, even the Giants fans that hooted and hollered around Manhattan on Super Bowl night didn't muster any team songs. The fact that Americans sometimes devolve into the simple chant, "U.S.A.! U.S.A.!" also seems like a sign of extreme melody atrophy.

But even if it should happen, say, that a dozen people gather in a park on a summer's eve, and they all know the words to classics like "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," "This Land is Your Land," and "Down By the Riverside"—respectively, a patriotic song about God, a Woody Guthrie ode to America, and an African-American spiritual about peace—would they want to sing? Or would a combination of self-consciousness on the one hand, and diverging ethnic, political and religious backgrounds on the other, prevent them from sharing in all three tunes? Stadium singing succeeds because of numbers, and because the songs are fun and uncontroversial.

Today, the problem is not just that we don't know the songs—we don't know which ones we want to know. The National Association for Music Education addressed this reality with its Get America Singing...Again! campaign in the 1990s, which put forward 88 songs as a shared repertoire for Americans. Although the formal campaign has ended—followed not long after by another project urging people to learn the Star Spangled Banner and realize they actually can sing the national anthem—the songbooks are still for sale, and the list is still good.

In these divided times as much as ever, we need to do some singing and feeling together, united as both citizens and amateurs.

One new communal occurrence in contemporary life cries out for song: the post-shooting vigil. The event is inherently public and emotional, made for group singing. Think of Chardon High School in Ohio this February, where a gunman killed three students and wounded two. Or the shooting of 19 people in Arizona in January 2011, including U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. Or the massacre at Virginia Tech, in April of 2007, when a student gunned down 32 people. In news reports, we see photos of hugs and tears and shocked faces, and then candlelight vigils. These events, which apparently will continue, seem even sadder without the relief of song.

When, if not here, are blues and spirituals called for? Where, if not here, would they provide a measure of healing? Healing for all, not just the performer with a guitar at the front of the crowd. Perhaps the vigils will inspire a powerful new folk song—one that's easy to sing, memorable, "viral"—to be written.

Colin Goddard, a survivor of the Virginia Tech shooting who went on to become an activist against gun violence, said he couldn't remember communal singing at any of the commemorative events he's attended. At the yearly anniversary of the Virginia Tech shooting, though, several trumpeters stationed around the campus play Taps in a round, each starting a few moments after the other. It made him emotional just recalling it. In terms of songs, though, "I've probably received five or six songs that people wrote about Virginia Tech," Goddard said. "People have sent them to me." And they are posted on YouTube—but they remain more like individual artistic responses than folk songs.

Occupy Wall Street is another new phenomenon built for communal song. Music has been a major element of the demonstrations, now blossoming again along with springtime, but "not widespread songs we've been singing together," said Nelini Stamp, a Brooklyn resident and singer who's been involved since the beginning in September. Although they're more fragmentary, the protest moments involving song still have Stamp excited: from ongoing sing-ins at courthouses to resist home foreclosures, to the night when Occupy was evicted from Zuccotti Park in November, when dozens of arrested activists sang "Stand By Me" and "With a Little Help From My Friends" in the halls of central booking. But she feels the need for original songs that everybody learns. "The next step will be, how do we create our own songs? As this year goes on, and things grow, we'll start to see that play a bigger part. There's a need for it."

To be sure, musicmaking is alive and well in America. The YouTube platform for performance sharing is just one sign. Online lessons have empowered wannabes to learn. Folks sing in religious settings as much as ever. People who enjoy singing get together in homes to make music with friends, and choral groups abound. It's the community-oriented, community-building, sometimes spontaneous kind of singing that's suffering. But yes, even those averse to singing in public may do it more than once a year. Likely in a bar. Drinks help, of course, and so do pop songs with a catchy chorus. If people want to sing "American Pie" or "Come On Eileen" or "Jesse's Girl" and drink a beer instead of "This Land is Your Land" and wave a flag, can you really blame them?

"I don't know if they're the new folk music, but they're the new collective repertoire," says Dr. Will Schmid, the former leader of the music educators' association, who created the folk song list along with Pete Seeger. There is a difference in public-spiritedness between singing Billy Joel in a lounge versus Stephen Foster at a picnic, he said, but "I'm not too worried about that."

"Any singing is good singing. Anywhere we can find it. Those places become the new community centers."

Belting at baseball games is an example of something essential, Schmid said. "No one there is worried about whether they're good enough. That's a wonderful feeling—that's what I think we need to restore. That sense that: I'm good enough. I'm a happy amateur singer. I'm just going to let it out."

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

KAREN LOEW is a writer in New York.

THE ATLANTIC

Relieve Your Anxiety by Singing It

April 13, 2016

On my recent reporting trip to Brazil, I went on a hike and got bitten 40 times by an unknown insect.

The welts were larger than mosquito bites and were completely painless until they began itching relentlessly a day later. Worse than the physical irritation, though, was the fact that, as a health writer, I know about all the different diseases South American bugs can carry.

At the time, Zika was just starting emerge, but I was most worried about a different threat: Leishmaniasis. There are several strains of this parasitic infection, but the one in Brazil can damage the mucous membranes in the face, eventually causing the nose and mouth to partly disintegrate.

I know this because I sat in a Starbucks for hours on my last day in Rio, googling every study on leishmaniasis and saving it to Evernote, so that the team of international health experts who would eventually convene in a top-secret clean room and race to find the antidote could use them for reference.

Never mind that I don’t really have that kind of sway with the WHO. Or that it’s unlikely that I have leishmaniasis: It’s rare to see it in Rio, and only a few dozen foreigners get it every year.

Still, the transcript of my thoughts was: What if I have it? What I if I have it? How do you say, ‘Are phlebotomine sandflies prevalent in this area’ in Portuguese?

I was already starting to feel my cartilage go wobbly.

I Skyped my boyfriend. “You’re required to still love me after my nose falls off,” I told him. “Like that lady from The Knick.”

It’s around this time that I could have used an app called Songify. The app turns words that are spoken into a smart phone into a song, auto-tuned and set to music. And now, some mental-health specialists are using the tool to help people overcome obsessive, anxious thoughts like the one I was having. With its help, I could have made something like this:

The underlying principle is that singing your thoughts separates you from their meaning. Almost all people (something like 80 to 90 percent of the population), experience intrusive thoughts—weird little niggling things they don’t particularly want scrolling through their heads. But for people who have obsessive compulsive disorder or generalized anxiety, the intrusive thoughts can become frequent and crippling. With OCD, the thoughts tend to be bizarre, such as thinking that the air will contaminate you. With generalized anxiety, they might be more mundane, like the idea that you’ll be fired if you bungle a work presentation.

Our minds can be Debbie Downers because, evolutionarily, we are predisposed to dwell on the negative and let the positive drift into the background. Simply trying not to think intrusive thoughts doesn’t work. Focusing on something, even in a negative way, wires it even more firmly into our brains.

“There is no delete button in the nervous system,” said Steven Hayes, a psychology professor at the University of Nevada who has used Songify and other techniques in his practice. By telling yourself not to think about something, he says, “you’re increasing the number of associates that remind you of it.”

Instead, it’s better to treat them just like you would a silly, meaningless song. They exist, but they have little bearing on your life.

“There is no delete button in the nervous system.”

Songify was only released four years ago, and it’s even newer to the therapists who use it. But the process behind the Songify technique, called cognitive defusion, has been around for decades. Before the app came along, therapists would have their patients sing their worries to common melodies. Sally Winston, the co-director of the Anxiety and Stress Disorders Institute of Maryland, once treated a mother who would obsessively text her son to check on him. Winston had her sing, “Johnny is dead by the side of the road” to the tune of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Similar methods, like repeating an unwanted thought out loud until it loses meaning, or sticking Post-It notes with the thought all over the house, have also shown some success.

Thirty years ago, Hayes saw an older patient who was a devout Catholic. During mass, she couldn’t stop imagining the priest with penises growing out of his ears.

“As you try not to think that, you have to remind yourself of it to see if it’s gone away,” Hayes said. “And there it is again.”

Hayes treated the woman by having her think the penis thought over and over again. First, the thought became less distressing. Eventually, it became less real, too.

Songify was designed for entertainment rather than clinical settings. A Songify spokesperson said the company knew the app had been used to treat speech disorders in autistic children, but was not familiar with its use in anxiety disorders.

Winston said the song technique works better than stress-management, distraction, or breathing exercises. A study out this month found that various defusion techniques, including singing the unwanted thought and saying it in a cartoon voice, reduced the frequency of the thought while making it less believable. The strategy worked better than both the control and another strategy called “restructuring,” in which the person tries to come up with an alternative thought.

Mark Sisti, the director of Suffolk Cognitive-Behavioral, has been using Songify for two or three years now. He said it tends to work best with people who realize their fears are slightly irrational, or at least are being over-thought. (Someone who just lost his job and is facing very real worries about making rent, for example, might not be the best candidate.) In addition to making the thought less foreboding, Sisti thinks Songify might work by “lighting up” different parts of the brain—the regions associated with music and pleasure, rather than fighting or fleeing.

Hayes has also used singing for other mental-health issues, such as depression. He occasionally has his therapy groups perform “depression operas,” with arias that go, “I’m really sad … I’m really really sad.” Other people put their worst thoughts on t-shirts, or send themselves emails that say, “Did you know you’re unlovable?” “You start playing with your own dark side and give yourself some distance from it,” Hayes said.

The process can seem perverse, since some of the patients’ fears—financial ruin, the death of family members—are quite serious. (To use my example, leishmaniasis is a serious scourge that afflicts poor people all over the world). But worrying obsessively about those things won’t prevent them from happening. They’re “unanswerable questions,” as Hayes calls them, and cycling through “what ifs” only gives them fuel. The point isn’t to suggest that the person’s worries aren’t scary, says Winston, it’s to develop “a different relationship with the thought.”

The therapists usually wait until they’ve seen their clients several times before suggesting Songify. How long it takes to work depends on the patient’s symptoms, but Hayes said he’s seen improvement within weeks. The person might not stop having the thought entirely, but they’ll no longer react to it with trepidation.

And because of Songify’s distinctive, robotic sound, they might even feel better right away.

Right after recording a Songify, Sisti said, “the person might say, ‘an hour ago, I was upset, and now I’m laughing.’”

OLGA KHAZAN is a staff writer at The Atlantic.

THE ATLANTIC

Can Anyone Learn to Sing?

March 2, 2024

This is an edition of The Wonder Reader, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a set of stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight. Sign up here to get it every Saturday morning.

“There is nothing quite so vulnerable as a person caught up in a lyric impulse,” Roy Blount Jr. wrote in our February 1982 issue. What makes the situation even more vulnerable is to be among the group that Blount calls “the singing-impaired.”

Some research suggests that it’s easier to improve a singing voice than you might think. But even for those whose prognosis is hopeless, there’s joy to be found in the act of singing. Today’s newsletter explores how the singing voice actually works, and what humans can create when we sing together.

On Singing

Why the Best Singers Can’t Always Sing Their Own Songs

By Marc Hogan

Performing pop songs live offers a thrilling reward—if your voice doesn’t betray you, that is.

What Babies Hear When You Sing to Them

By Kathryn Hymes

And what parents gain (From 2022)

Everyone Can Sing

By Olga Khazan

Very few people are truly tone-deaf. Most just need to practice, a new study finds. (From 2015)

Still Curious?

How to sing, while only slightly overthinking it: In 2012, Maria Popova offered a technical guide from the German opera legend Lilli Lehmann.

“The singing-impaired”: Read Blount’s entertaining essay on his singing struggles.

Other Diversions

P.S.

Need some new music to sing along to this weekend? Check out our Radio Atlantic listeners’ playlist of songs about friendship.

— Isabel

Isabel Fattal is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where she oversees newsletters.

TIME

Singing Changes Your Brain

August 16, 2013

When you sing, musical vibrations move through you, altering your physical and emotional landscape. Group singing, for those who have done it, is the most exhilarating and transformative of all. It takes something incredibly intimate, a sound that begins inside you, shares it with a roomful of people and it comes back as something even more thrilling: harmony. So it’s not surprising that group singing is on the rise. According to Chorus America, 32.5 million adults sing in choirs, up by almost 10 million over the past six years. Many people think of church music when you bring up group singing, but there are over 270,000 choruses across the country and they include gospel groups to show choirs like the ones depicted in Glee to strictly amateur groups like Choir! Choir! Choir! singing David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World.

As the popularity of group singing grows, science has been hard at work trying to explain why it has such a calming yet energizing effect on people. What researchers are beginning to discover is that singing is like an infusion of the perfect tranquilizer, the kind that both soothes your nerves and elevates your spirits.

The elation may come from endorphins, a hormone released by singing, which is associated with feelings of pleasure. Or it might be from oxytocin, another hormone released during singing, which has been found to alleviate anxiety and stress. Oxytocin also enhances feelings of trust and bonding, which may explain why still more studies have found that singing lessens feelings of depression and loneliness. A very recent study even attempts to make the case that “music evolved as a tool of social living,” and that the pleasure that comes from singing together is our evolutionary reward for coming together cooperatively, instead of hiding alone, every cave-dweller for him or herself.

The benefits of singing regularly seem to be cumulative. In one study, singers were found to have lower levels of cortisol, indicating lower stress. A very preliminary investigation suggesting that our heart rates may sync up during group singing could also explain why singing together sometimes feels like a guided group meditation. Study after study has found that singing relieves anxiety and contributes to quality of life. Dr. Julene K. Johnson, a researcher who has focused on older singers, recently began a five year study to examine group singing as an affordable method to improve the health and well-being of older adults.

It turns out you don’t even have to be a good singer to reap the rewards. According to one 2005 study, group singing “can produce satisfying and therapeutic sensations even when the sound produced by the vocal instrument is of mediocre quality.” Singing groups vary from casual affairs where no audition is necessary to serious, committed professional or avocational choirs like the Los Angeles Master Chorale or my chorus in New York City, which I joined when I was 26 and depressed, all based on a single memory of singing in a choir at Christmas, an experience so euphoric I never forgot it.

If you want to find a singing group to join, ChoirPlace and ChoralNet are good places to begin, or more local sites like the New York Choral Consortium, which has links to the Vocal Area Network and other sites, or the Greater Boston Choral Consortium. But if you can’t find one at any of these sites, you can always google “choir” or “choral society” and your city or town to find more. Group singing is cheaper than therapy, healthier than drinking, and certainly more fun than working out. It is the one thing in life where feeling better is pretty much guaranteed. Even if you walked into rehearsal exhausted and depressed, by the end of the night you’ll walk out high as a kite on endorphins and good will.